Through integration, Germany remains safe for refugees

Public fears that refugees could turn to criminal activity are at an all-time high. But instances of crime among migrants in Germany are no higher than they were before the refugee crisis. In Hamburg, Germans and refugees alike are working to keep it that way.

By Max Greenwood

Additional reporting by Kristina Bosslar and Viktoriia Fomenko

Additional reporting by Kristina Bosslar and Viktoriia Fomenko

HAMBURG, Germany – In Syria, Kasem al-Ali was a teacher. In Germany, he's a refugee, who has spent the better part of the past two-and-a-half years being shuffled across camps in Hamburg.

But al-Ali, 32, has come a long way since he first arrived in the country. He learned German quickly, and worked as an interpreter while staying in Schnakenburgallee, Hamburg's largest refugee camp. He navigated Germany's asylum processing bureaucracy to expedite his way to his own apartment.

"I wanted to get out of Schnakenburgallee," he says. "I wanted my own home. It was bad, bad, bad. You couldn't sleep well. The food was bad. I wanted a normal life."

Today, al-Ali seems to have found the sense of normality that he once so desperately craved, playing on a handball team in Hamburg's St. Pauli quarter. It's a new take on something he knew well in his hometown of Raqqa. What's more, he's using it to help other young refugees like himself adjust to their new lives in Germany.

For the past two months, al-Ali has coached a handball team for young men who fled to Germany from Syria and Iraq. His goal, he says, is to help integrate them into German society, and to keep them out of trouble in their new city.

"People who played sports on a team back home, I want to give them a chance to play here," he says. "I want to work with the refugees, because they need that chance."

But al-Ali, 32, has come a long way since he first arrived in the country. He learned German quickly, and worked as an interpreter while staying in Schnakenburgallee, Hamburg's largest refugee camp. He navigated Germany's asylum processing bureaucracy to expedite his way to his own apartment.

"I wanted to get out of Schnakenburgallee," he says. "I wanted my own home. It was bad, bad, bad. You couldn't sleep well. The food was bad. I wanted a normal life."

Today, al-Ali seems to have found the sense of normality that he once so desperately craved, playing on a handball team in Hamburg's St. Pauli quarter. It's a new take on something he knew well in his hometown of Raqqa. What's more, he's using it to help other young refugees like himself adjust to their new lives in Germany.

For the past two months, al-Ali has coached a handball team for young men who fled to Germany from Syria and Iraq. His goal, he says, is to help integrate them into German society, and to keep them out of trouble in their new city.

"People who played sports on a team back home, I want to give them a chance to play here," he says. "I want to work with the refugees, because they need that chance."

Video by Max Greenwood

More than a million migrants – mostly from Syria and Iraq – fled to Germany in 2015 alone, hoping to escape conflicts back home. Last September, German Chancellor Angela Merkel declared that her country would place "no limits" on the number of migrants it was willing to grant asylum.

But many of those who find themselves in Germany often face a frustrating reality there, including long stays in refugee camps, bureaucratic paperwork in German – a language not spoken by most migrants – and a lack of personal comforts one afforded to them back home.

"Inside the camps, there's no communication, and people need help," says Torsten Niehus, the director of the Quadriga Youth Center in Hamburg's Jenfeld district. "They'll receive letters and notices in German, but they can't understand what it means."

Not long ago, Quadriga was a typical youth center, a place for kids and young adults to play and work. But last year, Niehus says, the organization began working with people in an adjacent refugee camp. Now, on a typical afternoon there, the center is bustling with frolicking children and young people – about 500 each day – and a cramped-yet-lively kitchen at the compound serves as a sort of social outlet where adults can laugh and talk as they prepare their iftar, the evening meal when Muslims break their Ramadan fasts.

For Niehus, the center is a place where migrants can find a shred of normality among the crate-like boxes in the camp where they sleep, and a way to alleviate the boredom and frustration that many refugees feel in their new homes.

"For a while, we were the only place they could go to," Niehus says. "So we offered them Internet access immediately, a kitchen. The status of the people has changed since then."

"Here, refugees cook for other refugees, and it is distributed it in the evening," he says. "It helps to give people a welcome feeling; it makes them less frustrated," adding, "Here, refugees feel safe, and they feel like they are taken seriously."

That sense of communication and cooperation, however, could be accomplishing more than simply making migrants feel at home. Niehus says he believes Quadriga's work with the camp could help people there stay away from crime and radical groups, recounting an instance when Salafist groups would come but were turned away from the camp.

"They tried to reach the people and get them on their side, but that didn't work," he says. "They used donations and food and clothes, but they realized when they went into the camps and tried to be in control that it wouldn't work."

But many of those who find themselves in Germany often face a frustrating reality there, including long stays in refugee camps, bureaucratic paperwork in German – a language not spoken by most migrants – and a lack of personal comforts one afforded to them back home.

"Inside the camps, there's no communication, and people need help," says Torsten Niehus, the director of the Quadriga Youth Center in Hamburg's Jenfeld district. "They'll receive letters and notices in German, but they can't understand what it means."

Not long ago, Quadriga was a typical youth center, a place for kids and young adults to play and work. But last year, Niehus says, the organization began working with people in an adjacent refugee camp. Now, on a typical afternoon there, the center is bustling with frolicking children and young people – about 500 each day – and a cramped-yet-lively kitchen at the compound serves as a sort of social outlet where adults can laugh and talk as they prepare their iftar, the evening meal when Muslims break their Ramadan fasts.

For Niehus, the center is a place where migrants can find a shred of normality among the crate-like boxes in the camp where they sleep, and a way to alleviate the boredom and frustration that many refugees feel in their new homes.

"For a while, we were the only place they could go to," Niehus says. "So we offered them Internet access immediately, a kitchen. The status of the people has changed since then."

"Here, refugees cook for other refugees, and it is distributed it in the evening," he says. "It helps to give people a welcome feeling; it makes them less frustrated," adding, "Here, refugees feel safe, and they feel like they are taken seriously."

That sense of communication and cooperation, however, could be accomplishing more than simply making migrants feel at home. Niehus says he believes Quadriga's work with the camp could help people there stay away from crime and radical groups, recounting an instance when Salafist groups would come but were turned away from the camp.

"They tried to reach the people and get them on their side, but that didn't work," he says. "They used donations and food and clothes, but they realized when they went into the camps and tried to be in control that it wouldn't work."

Video by Max Greenwood

The criminal question

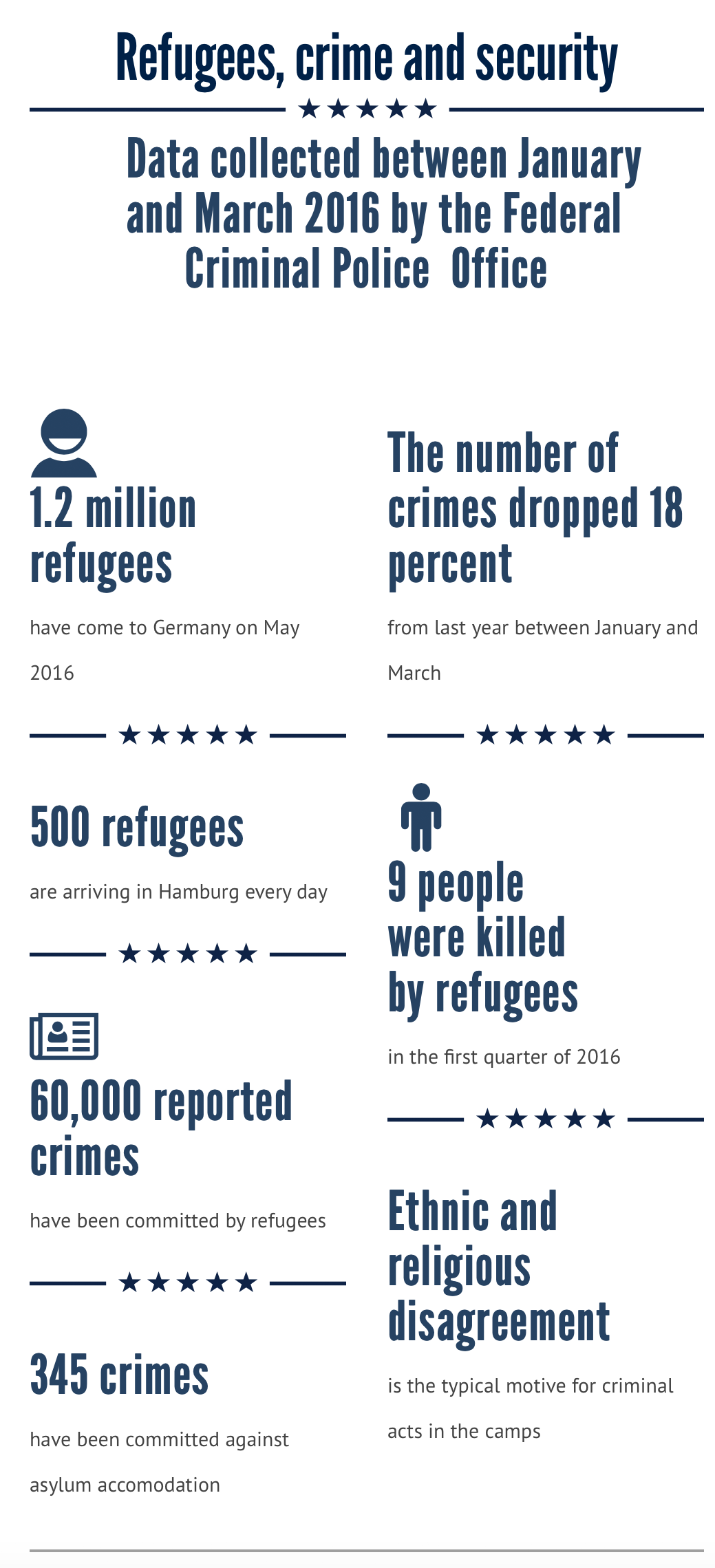

Overall, public fears that the influx of migrants to Europe has led to increased crime remain largely unfounded. A report released by Germany's federal investigative police agency June 9 found that crime rates among refugees were no higher than those among typical Germans, with crimes such as theft and forgery being the most prevalent.

And crimes committed by refugees appear less of a concern than those committed against them. The same report found 345 attacks against asylum accommodation between January and March – a sharp 263 percent increase from 2015.

Merkel announced in August that Germany would admit up to 800,000 asylum seekers within the year – a number that represents nearly 1 percent of the country's population. That's a far cry from the 85,000 refugees the U.S. announced it would resettle in the 2016 fiscal year, and more than any other country in Europe.

But Merkel has changed her tone in more recent months. At the G-20 Summit in November, she discussed the need to set quotas for migrants. And in January, she warned that asylum in Germany was only temporary, and that people fleeing Syria and Iraq would have to return once the conflicts in those countries have ended.

Overall, public fears that the influx of migrants to Europe has led to increased crime remain largely unfounded. A report released by Germany's federal investigative police agency June 9 found that crime rates among refugees were no higher than those among typical Germans, with crimes such as theft and forgery being the most prevalent.

And crimes committed by refugees appear less of a concern than those committed against them. The same report found 345 attacks against asylum accommodation between January and March – a sharp 263 percent increase from 2015.

Merkel announced in August that Germany would admit up to 800,000 asylum seekers within the year – a number that represents nearly 1 percent of the country's population. That's a far cry from the 85,000 refugees the U.S. announced it would resettle in the 2016 fiscal year, and more than any other country in Europe.

But Merkel has changed her tone in more recent months. At the G-20 Summit in November, she discussed the need to set quotas for migrants. And in January, she warned that asylum in Germany was only temporary, and that people fleeing Syria and Iraq would have to return once the conflicts in those countries have ended.

Meanwhile, far-right anti-refugee movements are growing across Europe, and in Germany in particular, many of which use crime among refugees as political fodder.

In Hamburg, however, crime committed by refugees doesn't appear to be a concern for law enforcement. Police don't patrol camps or areas heavily populated by migrants any more than other parts of the city, according to two Hamburg police officers, who asked for anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media and feared reprisals.

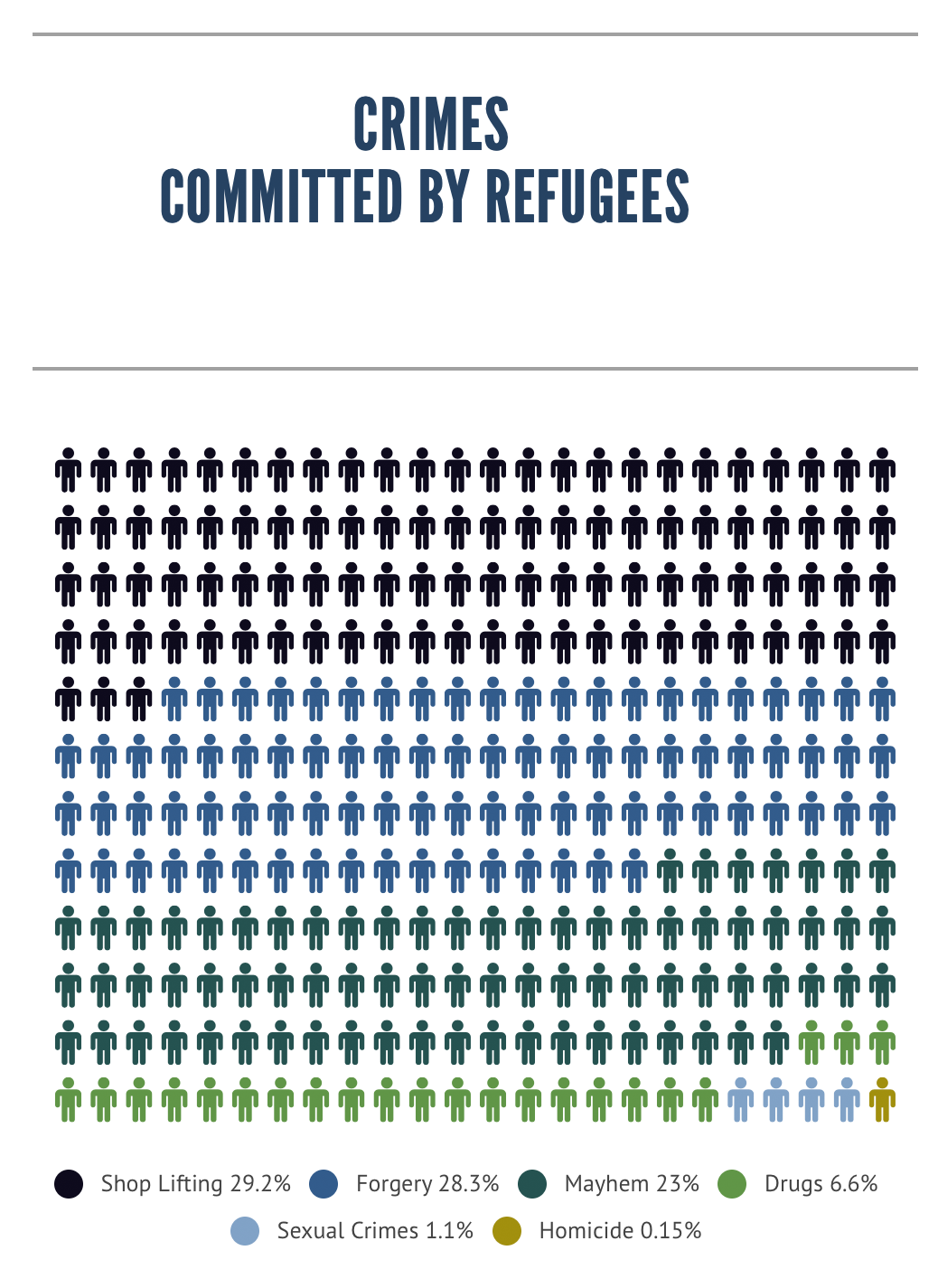

According to the federal police report, 69,000 crimes committed by refugees have been reported between January and March of this year. But the majority of those crimes – about 29 percent – were petty infractions, such as shoplifting and minor theft. And overall, Germany has seen an 18 percent reduction in crime in that same period.

In Hamburg, however, crime committed by refugees doesn't appear to be a concern for law enforcement. Police don't patrol camps or areas heavily populated by migrants any more than other parts of the city, according to two Hamburg police officers, who asked for anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media and feared reprisals.

According to the federal police report, 69,000 crimes committed by refugees have been reported between January and March of this year. But the majority of those crimes – about 29 percent – were petty infractions, such as shoplifting and minor theft. And overall, Germany has seen an 18 percent reduction in crime in that same period.

Graphic by Viktoriia Fomenko | Data provided by the Federal Criminal Police Office

While criminal activity among refugees and migrants in Germany remains few and far between, the officers said there are regular conflicts among refugee camp residents, usually fueled by boredom, lack of communication, frustration with camp life and subpar housing conditions.

Graphic by Viktoriia Fomenko | Data provided by the Federal Criminal Police Office

Coming a long way

Al-Ali considers himself one of the lucky refugees. He lives in an apartment, speaks German and plays a sport he loves with people he calls his friends. The last two-and-a-half years of his life have been tumultuous, but things have settled now, he says, and he wants to help others like him with handball.

That means keeping people away from crime, al-Ali says, to make sure they can stay in Germany. It means keeping them busy and relieving frustration with the stagnation and confusion of life away from home.

"They say if you become [a] criminal you don't have the right to stay in Germany. If you steal, or something else, you can't stay here," al-Ali says. "They tell the young people it's dangerous if they want to stay here. Refugees want to stay here, and criminal versus not criminal matters."

And while al-Ali has come a long way since he first arrived in Germany, he says he is not done integrating, but that he simply wants to help and be helped along the way.

"They don't come to me looking for help," al-Ali says. "They look for help with the Germans. I still need help, as well. But the people have to do something, and sports help."

Al-Ali considers himself one of the lucky refugees. He lives in an apartment, speaks German and plays a sport he loves with people he calls his friends. The last two-and-a-half years of his life have been tumultuous, but things have settled now, he says, and he wants to help others like him with handball.

That means keeping people away from crime, al-Ali says, to make sure they can stay in Germany. It means keeping them busy and relieving frustration with the stagnation and confusion of life away from home.

"They say if you become [a] criminal you don't have the right to stay in Germany. If you steal, or something else, you can't stay here," al-Ali says. "They tell the young people it's dangerous if they want to stay here. Refugees want to stay here, and criminal versus not criminal matters."

And while al-Ali has come a long way since he first arrived in Germany, he says he is not done integrating, but that he simply wants to help and be helped along the way.

"They don't come to me looking for help," al-Ali says. "They look for help with the Germans. I still need help, as well. But the people have to do something, and sports help."

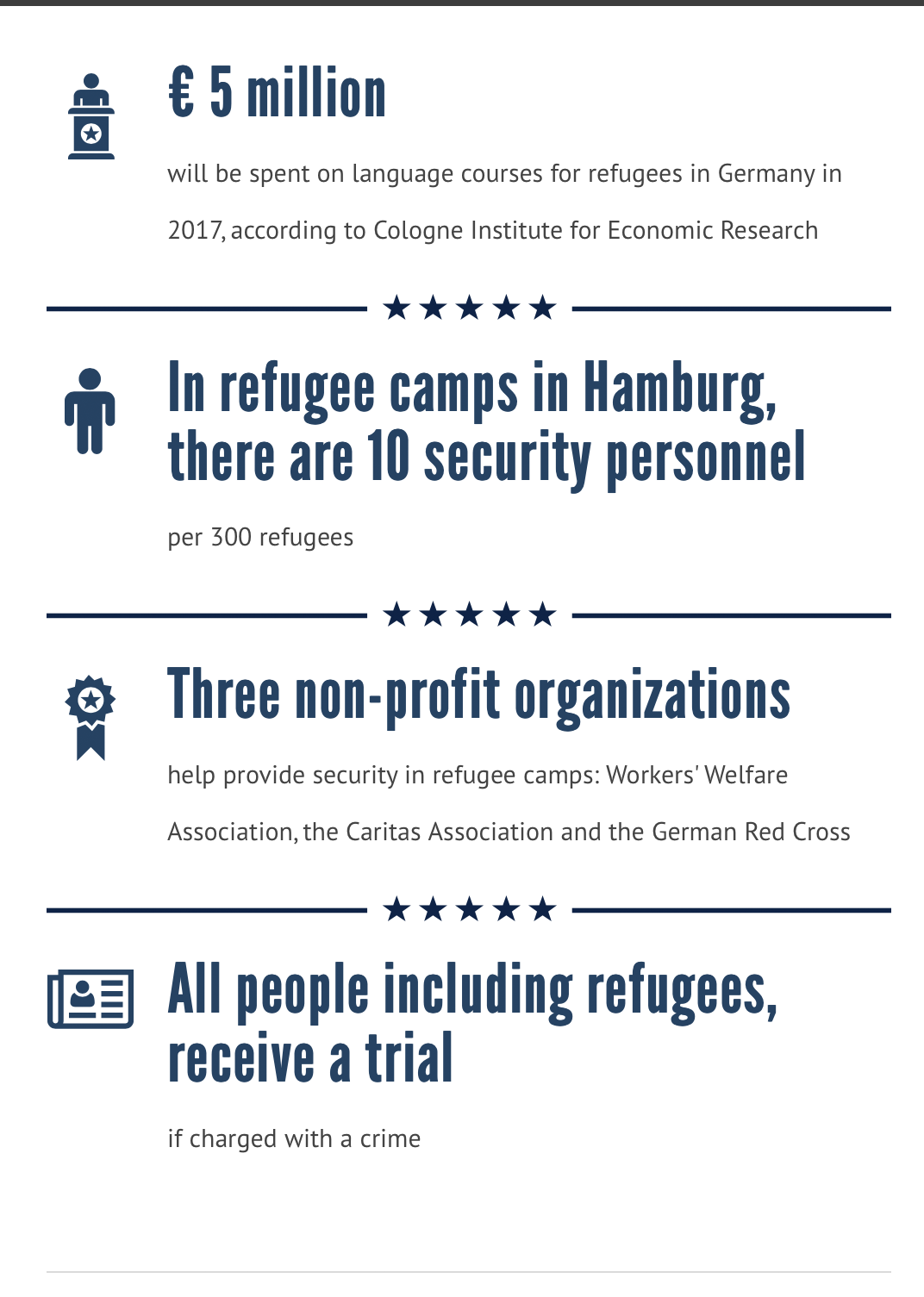

Graphic by Viktoriia Fomenko

Video at top: A refugee camp in Hamburg's Jenfeld district. About 500 people call the camp home.